Maurizio Ferraris – After life, what?

It can be useful to compare the video of the two dead teenagers with a rendition of this song on YouTube. I found one from the Sanremo Music Festival, with the full splendour of Al Bano and Romina in their heyday. As always with them, they appear to be talking about happiness and the simplicity of married life.

Happiness is more than just a glass of wine and a sandwich, as the pair suggested in another famous hit, where it is not difficult to identify a Christological undertone: happiness also means overcoming vana curiositas (dreaming of Hawaii) and inauthenticity, to gain access to true love, that between Al Bano and Romina, first and foremost, and for everyone.

But this is merely the most immediate interpretation of the song. It is clear that after this reconciliation on earth, there is another that awaits in heaven (“you’ve got to believe”), where past glory becomes silence and shadows, but where, on the other hand, there is a way to a better world and also “a more human way to say I love you”.

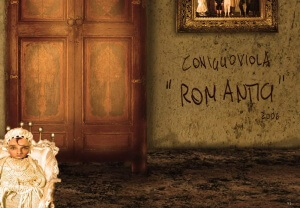

ConiglioViola has discovered Al Bano and Romina’s secret message, and brought it to light. The duo are talking about life after death. And ConiglioViola’s exercise points up the impressive similarity of the lyrics of the song with the words of Giovanni Raboni (from Quare tristis, L’opera poetica, I Meridiani Mondadori, p. 997): “Dopo la vita cosa? ma altra vita, / si capisce, insperata, fioca, uguale, / tremito che non s’arresta, ferita / che non si chiude eppure non fa male” (After life, what? Another life, / you see, unhoped for, tremulous, the same, / a tremor that cannot stop, a wound / that does not heal yet does not hurt). But I believe that the exercise does not stop here, with the revelation of the profound message conveyed by Al Bano and Romina. It is a little like the situation in The Others, the 2001 film starring Nicole Kidman, where for most of the film we think we are dealing with living characters who are afraid of the dead, only to find out that those we took for living are actually dead, and the film therefore looks at life through the eyes of death, not at death through the eyes of life. If I can be forgiven for a bookish, ostentatious reference, the situation recalls that of Federico Ruysch’s mummies: “As once from death / It shrank while yet alive, not otherwise / Shrinks from the vital flame / Our nature, naked waif; | Not happy, no but safe”.

The moral is a very simple one. Who ever said that pop flees death? Politics, and unfortunately often religion flee from it, so reluctant to remind us we will die, and even (in the case of politics) so quick to promise a hundred and twenty years of life. But pop cannot be said to avoid death; it looks it in the eye.

We have the triumph of death in songs like The End by The Doors (“My only friend, the end”), that in Apocalypse Now acquired even greater force when teamed with the dying words of Kurtz (“The horror! The horror!”).

Switching from twentieth century pop to its eighteenth century counterpart, we can find a bloodthirsty spirit, in the age when Frederick the Great lashed his soldiers with the cry, “Dogs, did you think you would live for ever?”. Traces of this can be found in unexpected places, such as the Marseillaise, where not only are we exhorted to “cut the throats of the fearsome soldiers” of the uprising, so as their “impure blood quenches the furrows” of the French countryside, but also to hope that on the point of death our enemies still find time to contemplate the glory of the forces of liberty (“Que tes ennemis expirants / Voient ton triomphe et notre gloire!”). All moving sentiments that give Mireille Mathieu’s ‘r’ added rasp and elicit the tears of both men and women in Casablanca.

And we have many eschatological pop songs, like those of Paolo Conte, which are at times nihilistic (“Areonautico è il cielo | vuoto, abissale sarà | senza orologi quel viaggio | tra stelle e cenere andrà” (Aeronautical is the sky | an empty abyss | a journey without clocks | between stars and ash), but at others more hopeful (“un’altra vita per noi | oltre il dialetto che hanno i santi, / arcano come certi amanti… / un’altra vita verrà, e un’altra vita sarà / oltre le lune e gli uragani / e le tue mani sopra le mie mani…”) (another life for us / beyond the dialect of the saints / arcane as lovers… / another life will come, and another life will be / beyond moons and hurricanes / your hands on mine…”), where God sometimes appears in person, refusing to lend you his bike.

And thanks to ConiglioViola’s deconstruction, Al Bano and Romina can now be included in this vein.

Maurizio Ferraris

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post