Martina Corgnati – Interview with Mr. Rabbit

M= Martina Corgnati

B= Brice Coniglio

1 Violet

MARTINA: It can be difficult to see how such diverse projects – as ConiglioViola has produced so far – could actually hook up with a unified vision of the world. This could be one of the aims of our conversation. And while we’re on the subject: should artists necessarily have certainties and visions? BRICE: I have no certainties or general theories about that. M.: But I’m not interested in general theories. I want to talk about you. What does ConiglioViola mean to you? B.: It’s not that easy to talk about… I mean: I think that ConiglioViola was a kind of project… a message of love or in any case a message, a stand-in for me… though at the beginning ConiglioViola was not just about me, it was a kind of child. M.: Your name is Coniglio, isn’t it? B.: Yes, yes, my name is Coniglio… and I often dressed in purple – although I think I prefer indigo – when I acted in first person I had a kind of security blanket – it was a purple top hat, because that’s a strange colour… M.: That you can never mention in the theatre; worse than the number 13, black cats or anything else… B.: So they say… I’ve thought about it a lot … but it is a colour on the margin, and that’s what counts. M.: It evokes many different things. B.: It is connected to something which I feel belongs to me: being never completely in yet never completely out; a role that corresponds a great deal to how I feel or have felt in my life, as a slightly borderline figure. This has caused me a lot of suffering but has also given me a certain perspective, it is something that grants me a particular vision – I don’t like the word “particular” – yet many people think they are special without ever having experienced the burden of being different. M.: It is a great strength B.: It’s something that makes you suffer but gives you a different vision… I think that to some extent this is my duty. What I mean – I’ll try to explain – is that I want to be what you call an artist, I know it’s a job, but I think that above all my duty is to try: what I have to do – and I mean this in a humble way – is to try and look at things from another point of view. This is something that not everyone can do, luckily for them. M: Don’t you think that all artists are in this position? B: They should be; but I don’t see it in the artist just in it for the money, and in view of that too much inside things. Being an outsider is hard, and taxing. It’s a kind of priestly duty that belongs to the artist, the wizard, the philosopher, the prisoner, figures that lie midway between solitude and other people. This is what purple is about.

2 Coniglio before Viola

M: How did you become an artist? B: I never set out to be an artist, even though I was viewed as having that typical kind of character, the cliché of the clown figure… but in actual fact the start of my life as an artist coincided with my withdrawal from life in the first person M: What did you do when you were living in the first person? You were at university weren’t you? Studying philosophy… B; Literature. But no, I wasn’t doing anything special, it was just a magical time in my life… I was very Dadaist. M: In the sense of breaking away, not accepting things… B: Yes, I was very amusing. I did some pretty surreal things, like with people I met in the street… because that was my way of communicating – crazy, naïf. M: In so far as it wasn’t an act. B: No, it wasn’t, but it could have turned into one because theatrical mechanisms came into play. These were useful at the start but then they became all too easy. But I think there is a substantial difference between the mask and the character. The mask is a cover-up, it hides the face, you can put it on and take it off at will. But you can’t get rid of the character, it clothes the soul skintight, it’s not a hiding place, but a suit of armour that allows you to show your authentic self. M: But you enjoyed stirring things, was it about attracting attention to yourself? B: Yes, of course, but for me the most important thing was doing something inappropriate in a given setting to observe the reactions I elicited, and to really enter into contact with people in an unconventional way. M: But why? B: Because I feel unsure around conventional behaviour, that is, I am not sure of people’s sincerity, shaking someone’s hand, being introduced… I’m not, and I wasn’t, sure that when someone greets you they really want to, that it has any meaning. M: You’re right. B: I am, and I was, terrified that there was no sincerity in all these gestures that are in some way expected. And I needed to feel totally sure of the sincerity of everything I did. I don’t feel that need so strongly now, which, when you think about it, is pretty serious! M: But what did you want to do you when you grew up? B: Anything but be an artist, a visual artist: what I do now. M: But why? B: I can’t draw, I have no manual skills… I just make a mess of the paper, I’m no use at it. Actually, do you know what? I don’t think I have a particular talent for anything… M: But you’re a computer genius, aren’t you? B: I don’t know, it was purely a chance thing. I’d never had a computer, it came into my life as something that I had always kept at a distance. M: What about music? B: …possibly the most powerful art form M: Your favourite, in any case. B: Yes, even though I don’t actually listen to it much, because I can’t manage it – if I listen to music I don’t get anything else done. M: What kind of music do you like? Italian music from the 80s, for example? That even became one of your projects, Recuperate Le Vostre Radici Quadrate. B: Yes, it’s a project… Anyway, I don’t like the question so I will answer as a formality. I love any kind of music that has some kind of intrinsic theatrical quality… This concept connects even forms of expression that are very different. Enough said.

3 The same outsider dimension

M: Do you like travelling? B: Yes, travelling is part of my way of experiencing the world: only while travelling was I able to fully and justifiably experience the feeling of being a foreigner that I felt at home too. At home that attitude could end up being problematic, but while travelling it was entirely legitimate. M: You travelled in your own way. B: Always alone. I would leave without any money, never knowing when I would be coming back… I would be looking for something, but nothing specific… nothing really. M: Nothing fundamental in any case, it wasn’t that important for you as an artist… B: No! because I wasn’t an artist, I never wanted to be an artist, and it was only after I’d been an artist for three years that I discovered that what I was doing could become a job. I have to make that distinction. M: Sorry, but when did you become an artist? B: When I changed my point of view. Quite simply: at a certain point I found myself in a different position, in a city that was not mine, small, very conventional, in a setting that could be described as hostile, and at the same time, as a way out of that, I found these “substitute” forms of sociality, like the net. Not just that, but for the first time in my life they enabled me to create something concrete and almost tangible, enabling me to be more than just someone who talked or thought a lot. Now I was someone who could lend shape to various ideas very easily and for free. It was then that I started being an artist, or rather producing works. M: When was it? B: That was 2000, 2001. I had been given a computer and a relative asked me to find someone who could make a website… in the end I learned to do it by myself. It was a website for spare parts for articulated lorries: strange, beautiful objects! Really beautiful. Back then doing websites was something new, it was like creating theatre sets, with the unknown quantity of who would appear on that private stage, and when and how. So, at that point I started doing my projects on the web, and what did I think about… what’s in it for me? I thought: maybe I’ll become a web designer and these projects will give me publicity… because media attention was one thing that I got that right away. M: How did that come about? B: By churning out a series of bizarre experiments, including a foot-fetish site, a pseudo porn site called Pornella, the site for the pop group Modho and a sort of virtual house. And then La meditazione di Yolanda, the first ever site for meditating online. That was an important intuition. M: What year was it? B: 2001, I was living in Barcelona. You enter the site guided by the robot from Metropolis, rechristened Yolanda. I wanted to introduce the idea that the internet could become a prosthesis not only of the memory but also in some way of the deepest layers of our consciousness. I think time proved me right.

4 Net.genius

B: That was the start. After that there were other net.art projects, a great one called Secret.room, then Un’estate al mare… each one explored something different. M: How did you go about working? B: I used technology in an unusual way. At the start all new technologies get used automatically. Think of the TV shows in the 80s, they used special effects simply because they were something new. While ConiglioViola, for example, used Flash without Flash graphics. This led to the first experiments with video, the “Dis.soluzioni” trilogy set to the Modho song, created simply by animating photos with Flash. These works, done using very simple tools that no-one has ever seen again, still retain their poetry. One thing that is a priority for me, however, is maintaining a competitive relationship with the software, because when you work with digital technology the software is always a silent coauthor, you have to use it without getting used yourself. M: In this context too, you have a borderline, transversal approach. B: Yes, acting in that way often means you can be ahead of things. In fact three years later that approach to graphics became the main style on the web. Recuperate Le Vostre Radici Quadrate came about two, perhaps three years before Italy got obsessed with the 80s. The same thing happened with Nous Deux and stereoscopic imaging. And using digital body art to turn yourself into a child. M: At this point we can say you are an ingenious IT experimenter… B: I’m interested in magic you see… And I believe there is a deep-seated affinity between digital and spiritual… firstly because they are both to do with immateriality. My relationship with art springs from the digital world, in the sense of a metalanguage, a sort of metaphysical code for ordering reality. M: What do you mean? B: Painting works with colours; sculpture with stone, whatever technique you take works with some kind of medium, while digital art works with a language made up of zeros and ones, it’s immaterial, numerical, a metalanguage… I am interested in that and the opportunity it gives me, that is to roll out the same idea in every form. The same “word” becomes music, video, photography and then even acquires totally different forms: theatre, installation… opera! Multimedia art par excellence. The digital dimension is a tool that lets you get back to that kind of thing, I would call it renaissance-like… and it was the tool that solved my dilemma of “what to do when I grow up”, the nightmare of having to specialise in something or be defined by my job.

5 Making worlds that can be shared

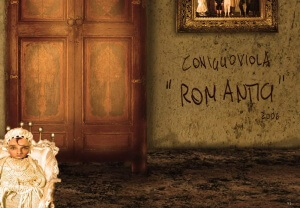

B: In my view art is connected to operative dimensions of this kind. Doing art means being a sorcerer: the figure of the wizard interests me, the way he is “on the outside”, taking on the suffering of others. M: The wizard as analyst? B: No, not an analyst, analysts have ways to keep things at arm’s length… M: Analysts are rational. B: The creative wizard, who takes risks. Yolanda is a project that refers to a mystical dimension, and the video Rebus is a kind of magical operation, an initiation rite you have to undertake to get access to the work. Then there is the idea of immersion, taking people and putting them into other worlds. “Making Worlds”, as Birnbaum says. M: Once again, this is a general issue in art. B: For me it was this wizard-like position – and ConiglioViola resembles me in this: ConiglioViola is to art as I am to the world – very central and very eccentric. M: The impression I get is that you are shy. No, seriously! That you are obviously a consummate charmer but someone who puts out something authentic, not an act. There’s a game being played here – but this position of eccentricity might also be connected to your shyness – people who are shy are a bit eccentric too, aren’t they? Someone who has to stay on the margin, out of fear and lack of confidence, a bit childish but also very grown-up, someone who is able to take on responsibilities. And in your work you have taken on a great many responsibilities. B: Yes, my way of being so “out of things” was in response to my shyness. At the beginning I was constantly challenging my limits, my difficulties, then slowly things started to come between me and the world, and when I found myself surrounded by this wall, art became my replacement for direct relations. I say it with great regret, but I chose this, it’s what I wanted. M: So we come to ConiglioViola B: but then I started to miss that suffering, that positive destructiveness, because it was actually working against the barrier, the limit. I have a need for complicity, to bring someone else into my world, alas! In both life and art, those who come and see my works have to enter another world. I used to try and draw people in, to involve them totally, I wanted total osmosis, to give totally – but now maybe I have less faith in this. Have I changed so much? M: I don’t know how much faith you have. But in my view, what is arguably your most lyrical and atmospheric project touches on this very subject, being built around sharing as a narrative as well as being an autobiographical strategy… I’m talking about Nous Deux. B: Just a second though, to talk about this I have to go back to ConiglioViola, which sprang from an idea of mine, a need, and in the beginning it was almost like an anonymous creature crawling around the web, with no-one knowing who had given birth to it. At a certain point, however, I felt the desire to share this project with the person I was closest to. There was this obsession for the number two, which for me is a perfect and impossible number, as my astrologist told me. Well I wanted to go beyond the dream of “forever”. All artists tend to project themselves into the future, because their works inevitably outlive them. That wasn’t enough for me, I wanted to project my relationship, artistic or personal, it’s the same thing for me! Into the past too, so I could really say “forever”. Nous Deux is an imaginary autobiography. Mine and that of my then partner in crime. There are 11 images (because 1+1=2) telling the story of two naughty children, us two. They were created by manipulating current photographs, by means of what I describe as digital body art, that I used a year before in the video Romantici. The eleven works were exhibited using a stereoscope, a very old technique that once again recalls the number two… How many times, when we meet someone important at a certain point in our lives, do we wonder what would have happened if we had met somewhere else, at another time, in another era? This is the tragedy of being able to live only one existence, one thing at a time, something I have always been obsessed with (and I think it shows a bit in ConiglioViola). It is also the dialectics of possible worlds. This is what I use art for, to live the lives I haven’t lived, as well as escaping from my own. Beforehand, in the PAC garden, you quoted the phrase by Battiato… “abbandonare il pianeta” (abandon the planet). The heart of Nous Deux is an image, tender but brutal, of the two children in prison, which also appears in the video Le vent nous portera. Here prison is the metaphor for the determination of our existence, Bastille-like… and art is the hot air balloon/rabbit that the children dream of escaping on. M: Brice, can we talk about you and your work now? B: The point is that I have no interest in documenting something that’s in my head, there’s no point in that, what I want and hope to do is create worlds that can be shared.

6 The audience is fundamental

B: As I grow up in the art world I am acquiring parameters, tools and tactics. I don’t think that’s wrong, because if I want to share a world, at least now I know what type of world to share, the characteristics that the world should in order to be shared and used, metabolised by the art system. All of this is the aesthetic, the appearance, the way in which an idea becomes a phenomenon – it’s a stupid thing to say. What I have to do is create bridges with the people around me. Because the audience is fundamental in my work, no doubt about it. M: And fundamental in your life too. B: Yes, you see, many artists don’t say it but the audience is always fundamental, actually I think it is even more fundamental for those who don’t say it. M: What audience? B: Not long ago I changed my mind about the people I want to talk to because in the art world there is a different audience to what I was used to dealing with before, which was more heterogeneous. I found this out gradually. I think that my work has to be accessible, art must be close to things… But that’s a different question. In the contemporary art world it often happens that the “appearance” of a work ends up hiding the contents, and this is due to facile prejudice, a limit common to many of those in the trade. Yet I believe that the real work of art should be sought right there, in the difficult balance between what is apparent and what is hidden. Recuperate, for example which also played around with music, famous songs, and was a very complex project… paradoxically it was more difficult for the art audience than the “normal” one.

M: What do you mean by a normal audience? B: Not specialised – the audience I gain access to when my works become theatre pieces, for example. In those situations I have seen it all, from the pensioners at the Grinzane Festival to the 15 year olds who didn’t even know the songs we were redoing and thought they were new tracks…

7 Inflatable Tvs

M: To get back to Recuperate, where do square roots come into it? B: It is a nonsense title, undoubtedly I liked the play on words, and the special effects, the allusion to maths. M: Why the 80s? B: The last legendary era! And I am passionate about the women from that era, I liked the music, naturally, but in particular I was interested in the fluttering legend of these figures. Unlike Vezzoli, who I am always likened to for this project, this is not a nostalgic evocation, but a dialectic with the present. In that period, unlike the present, those female figures were legendary, they were there, like symbols. And I wanted to refer explicitly to Italian music, home-grown music – because I wanted to use something of my own, and not be using foreign music. These performers convey a strong rapport between music and image – and therefore between Dionysian and Apollonian. This has the power to create an identity. M: Have you ever made music videos? B: Some, a really funny one with Loredana Berté. But I prefer to remain an artist, so no-one can tell me to show the guitars and no-one asks me… then I would probably be asked to make videos for tracks I don’t like, no way! That would be impossible. I have made videos for songs that never had them. Recuperate explored that very relationship between music and image which was typically 80s, but also mine: with this music submerging you in a hazy world with the potential for thousands of images, and then associating one image with a track, according to a precise strategy. A precise choice for something that could be infinite, yet at the same time a door open on the flow of identification. M: That relationship has now broken down. What do you think of Big Brother? B: I think it’s a piece of clever bullshit, the programme is terrible but the idea was a turning point. Here television is a mirror of daily life, whereas before it was like theatre,where I can watch something that is “above” me – and it was to get back to that that I did Recuperate. As an exhortation. The set for the show had a huge inflatable TV, which contained the theatre, as I was saying M: Great idea. B: Sometimes these great ideas come because the set has to fit in the boot of your car.

8 Musical wallpaper

M: Is the rabbit inflatable too? B: Did the rabbit come before the TV? I can’t remember… M: Because the rabbit is big, it wouldn’t fit into the room we’re in now B: Nooo… M: Why did you make it so big? B: Megalomania M: You made it for Venice… B: No, in actual fact it came about before then, for the Biennale dei Giovani Artisti a Napoli. At that time the rabbit had a green belly and people could go in there and cuddle up together. Using the chroma key technique I projected the scenes outside on surreal backgrounds. M: Do people get close in the bellies of rabbits in general, or because rabbits are always at it… or because of the colour green? B: Because with green or blue you can use the chroma key technique, the technique I use for my videos. But this was all live – it was a VJ set – when you remix your images live, and project them, not holding them back and just letting them flow… it’s hard work but this VJ set, which was all the rage at the time, worked a bit like wallpaper, which is how it should be, because the music that DJs play is exactly that. I don’t mean that in a negative way – in actual fact it was a historic turning point: when music became a soundtrack, a continuum, whereas before it had an ending, a structure, a crescendo. A DJ set, on the other hand, is a loop: musical wallpaper. To create a set that would really get into people I got the people to get into the set, and turned them into protagonists.

9 From the other side of the sea

B: That was the birth of the Coniglio. Then it got a name: I asked a girl during an exhibition what to call it and she suggested Gesù (Jesus). Prophetic. In fact in 2007 when I wanted to make some noise at the Venice Biennale I decided that I would make it “walk” on the water, complete with wings, with an eyepatch to turn it into a pirate, mocking the Lion of St. Mark’s and that… M: Why, because the Lion of St. Mark’s was a pirate? B: It was a parody – it had wings. From the allegorical point of view, the rabbit and the lion are diametrically opposed, one is courage and the other is fear, right? So now I’m going to make a rabbit more aggressive than this lion. The lion in this case became a symbol for the art system and… M: Were you already tired of it or did you still want to upturn stereotypes? B: I wanted a rabbit that would be more ferocious than the lion. Which seemed tired, blindfolded, bent over. So it was a spectacular, amusing gesture, which was also autobiographical, because that’s the way I felt, coming to art from the other side of the sea, who knows which one. You’re in the sea, you don’t know where you set off from… but you’ve got there and I wanted to arrive in that way: with a joyful but critical project, explosive and sensational, destructive and sensational: that’s what ConiglioViola is, that’s how I see it. The attack was directed to art – it was a warning: look, art has to look outside itself, not just to itself. It’s terrible when art only looks to itself, it’s a narcissistic mechanism… and you know what happened to Narcissus. M: He fell into the fountain. B: He committed suicide by dint of falling in love with himself, quoting himself… M: Don’t you run that risk yourself? B: Why… me? Yes, we all run that risk. Naturally. I try not to take inspiration from the system, but from something outside it… M: A while back I said something – I’m not sure why I said it, but I am totally convinced of it: the question of responsibility – in my view you are very responsible, when you work on a project you don’t let anything get in your way, you put everything into it, you want a lot and you use lots of different languages. In other words, you feel the need to do something full, not for yourself but for others. This is what being responsible is about. B: … M: You want the people that end up in front of your work to be happy. B: Yes. Happy or in any case that… that’s the role of art. If not what use is it? Art isn’t a book of philosophy. If it was a treatise… it would be a really bad one… so when I see artists who think they can explain something or make a documentary, bah! What is that? There are other people who do that better than you. As much as it’s still in fashion, making documentaries or explaining ideas… I’m just not interested. Works must stir something up, hook you in or engage you, reveal something, envelop you, fling things open. You have to work with the sense of wonder.

10 With a sense of wonder

M: You produce performances but you don’t operate in the first. B: Well it depends. I could operate in the first person, but perhaps I am too shy right now. I used to put on performances every day, without a stage, therefore more risky… I made gestures, risked being beaten up at times, then in the end I didn’t get beaten up, I don’t know why, I think people maybe understood that my gestures were innocent. In any case performance art interests me up to a point, the only piece I really did was the pirate attack. For me the rest is theatre. And if I produce proper theatre shows I want professionals on stage. M: but you risked in another way, when one of your works was at the centre of a national scandal, and even caused an exhibition to be cancelled… Ecce Trans caused a massive scandal, everyone was talking about it, it started arguments, people taking stances, furious comments, TV reports. You messed up big time. I’m really not into provocation for its own sake – contemporary art is chock-full of it nowadays, and I see that as a symptom of its weakness, its crisis point, its emptiness. So can you explain what it was you set out to do? B: Pasolini said that when the work of an artist is honest it always creates scandal because the artist’s vision bursts in on the lives of people. You see, when I was invited to take part in that exhibition, (which incidentally was not a great exhibition, or a necessary one) I got to thinking that I was one of the few living artists in the show and that it was therefore my duty so say something about the present. I don’t care for gratuitous provocation either! Provocation is only worthy of the name when it reveals truths, otherwise it is just vulgar, offensive, facile and useless, there is so much of it around these days, it just ends up being about getting publicity! That time, however there was an emergency that had to be addressed, and I had the opportunity to do it. In that year (2007) the issue of homosexuality was a thorny political issue in Italy, and to talk about sexuality I wanted to focus in particular on transsexuals, who in my view are the only figures that effectively are not integrated, that are outsiders in our world. There was that ridiculous case, a simple photo in which Sircana, possibly quite by chance, was driving past a transsexual, and it caused such a scandal… The paparazzo who took the photo had sold it to an important publisher who however did not publish it… I got the photo off the internet and manipulated it in a fairly simple way to replace the figure of the transsexual with that of Christ, taking inspiration from a passage of the gospel according to Matthew, which was also, not incidentally, a favourite of Pasolini’s. In that passage Jesus, who in the first place was a great provocateur, a rebel, says that we can see him in every person “on the margins”. So the image of the transsexual in question, that caused such a furore, became a perfect Imago Christi. But there was another level to it. I decided to put a price tag on the photo, €100,000, which was what the original paparazzo was paid for it. This was to highlight the stupidity of contemporary journalism, that feeds off easy scoops to distract our attention, and a way of underlining how an artist can create an even more scandalous revelation (on sale at the same price as the original, and with the price there for all to see!), because the artist’s camera, even when it is directed towards reality, captures details that escape the common eye. In the end the furore that Ecce Trans created showed that I hit the spot… but the scandal was not in the work itself, which was orthodox and faithful to the Gospel, but in the judgement of those who condemned it from behind a shield of facile, hypocritical moralism. M: you paid a high price for all this B: …honest traders always earn a bit less! M: And now, what do you want to do? B: I want to invent a ship – not a pedalò anymore – a flying pirate ship, I don’t know, with as many people as possible on board, each with what he or she can bring. I want to be even more multimedia in a way: it is very difficult from the practical point of view, but it fulfils my need. To trace new routes to wonderland.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post